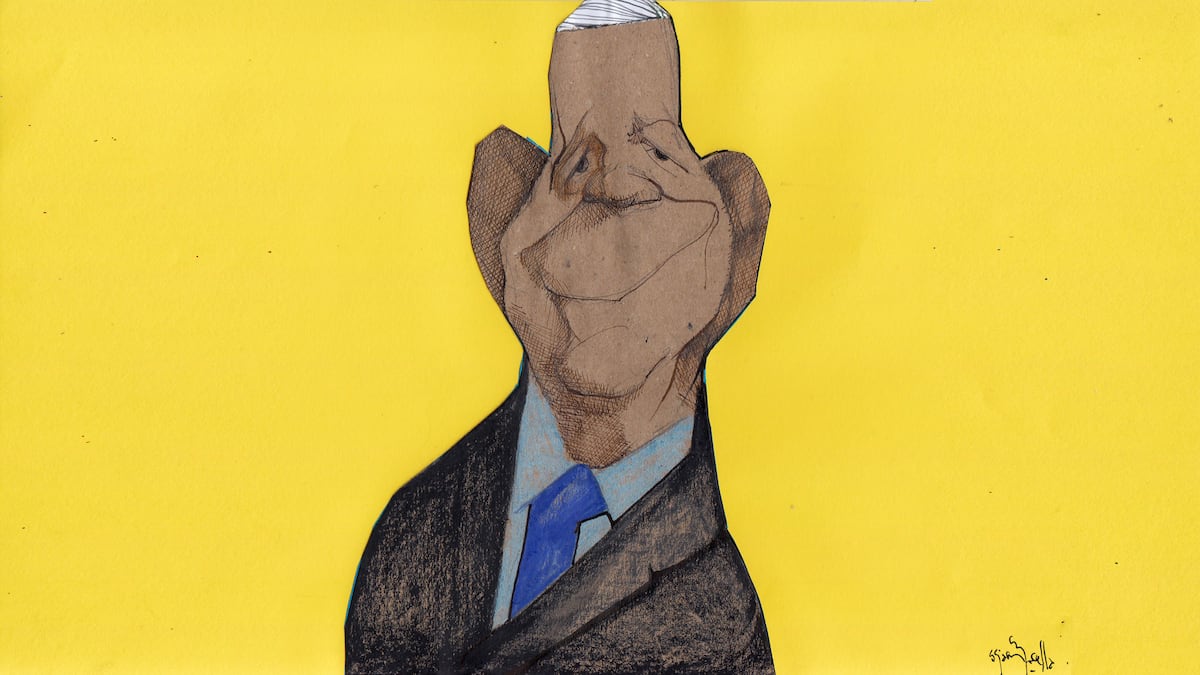

Edmundo González Urrutia, unanimous man

The young ambassador Edmundo González Urrutia was one of those responsible for the return of Felipe González to Spain, in the mid-70s, at the beginning of the Spanish transition. An effort that was coordinated by the then President of Venezuela, Carlos Andrés Pérez, and that González Urrutia remembers well: “I was on a mission in Geneva, and President Pérez was also on an official trip. At one point, Foreign Minister Escovar Salom asks me: ‘Come to this hotel, this person will be waiting for you so you can get on the president’s plane because he is leaving for his country. You find him and take him.’ That’s what I did: I introduced myself to him, I saw who he was. I put him in the back of the plane and we took him to Spain. When we landed in Barajas, President Pérez jokingly told Adolfo Suárez: ‘I brought a stowaway here for you.’ “This is how I took Felipe back to his country.”

A diplomat with a long career in Venezuela’s Foreign Ministry, Gonzalez Urrutia, who is a candidate facing Nicolas Maduro in the presidential election this Sunday, was Venezuela’s ambassador to Algeria, Tunisia and Argentina. He is a professor and writer with a somewhat intellectual bent. He speaks four languages. He worked on Venezuela’s inclusion in Mercosur and was temporary secretary of the Ibero-American Summit of Nations, held on Margarita Island in 1997.

With this service record and numerous studies and contributions to the programmatic work of the Democratic Unity Roundtable (now Unitary Platform), it never ceases to amaze how unknown Edmundo González was until recently. Edmundo González Urrutia did not want power, he did not seek it: power has knocked on his door. Maria Corina Machado, the absolute leader of the opposition, thought of him when she and the next person she appointed, the historian Corina Yoris, were disqualified. Then it was Edmundo’s time to reassure. At this stage of his life he did not see himself on a mission of this level. Finally, he agreed, and here he is, at the pinnacle of history.

There is an important reason why Edmundo is not seen: he is a shy boy. Very disciplined and hardworking, he is reluctant to argue vigorously and does not like to attract attention. Until the demands of politics knocked on his door, it could be said that he was “the master of his house”: a man living a family life, attached to his wife, daughters and grandchildren, a man of academic routines and learned procedures.

“As a boss, he is a very respectful, kind, friendly person. He can seem distant because he is shy. I worked with him in the Chancellery, I was one of his assistants. He is a very good diplomat. A good tennis player. He likes good food. “He really likes music, The Beatles, Celine Dion.” This is how one of his personal friends from the Foreign Ministry days, who preferred not to be identified, described him.

“González Urrutia was a good friend of US diplomat Thomas Shannon. ”He really liked playing tennis matches,” the source recalls. González Urrutia is the great-grandson of Wenceslao Urrutia, Venezuela’s chancellor during the government of Julián Castro in 1868. Those close to him agree that he has a sharp sense of humor in his closed circle of friends, although he tends to be somewhat laconic and distant in formal places.

“Edmundo is a lifelong figure of the Venezuelan diplomatic service, a career diplomat,” comments historian Edgardo Mondolfi, who worked with him at the Venezuelan embassy in Buenos Aires.

After graduating from the School of International Studies of the Central University of Venezuela, he spent his entire career in Venezuela’s Foreign Ministry. González Urrutia was part of the country’s diplomatic service, even in the government of Hugo Chávez. Career diplomats at the Foreign Ministry were progressively replaced by personnel loyal to Chavismo’s ideological principles and hegemonic objectives. According to sources, he resisted until 2006.

“I would say he is a very calm person. It is not usually changed. Take care of the details while moving forward. He likes to write, he has intellectual concerns. He is the author of some important biographies, such as the one he wrote of the historian Caracciolo Parra Pérez, and has compiled several books on international political issues,” recalls Mondolfi.

Although he has been very careful not to antagonize María Corina Machado, who is campaigning for her candidacy, González Urrutia certainly has other styles in politics and another school of procedure, and he has tried to find spaces to listen to his interlocutors and form his own perceptions of his new responsibility.

Some of these politicians, such as Ramón Guillermo Avelado (for a long time, executive secretary of the MUD) or Ramón José Medina, hold opinions different from Machado’s. González Urrutia is not an extreme figure: his thinking is close to Christian democracy, and his personal style naturally leans towards creating spaces for dialogue, political realism and the search for consensus.

Although he has advised various factions of the opposition, González Urrutia is one of its officials who do not work for parties, but rather for the unitary bodies that the opposition puts together as a political faction (formerly the Democratic Unity Roundtable, now the Unitary Platform), which are generally small. During these years, without opposition, González Urrutia has been very close to the Fermín Toro Institute of Parliamentary Studies, founded by Aveledo, and has been supportive of the Platform. In this work of professional support for the needs of the Unitary Platform, González Urrutia has worked closely with leaders such as José Luis Cartaya, Gerardo Blide, Medina and Fernando Martínez Mottola.

“He is a gentleman,” says one of his assistants, who preferred not to be identified. “Sometimes he is a little impatient,” a characteristic that matches the versions of some journalists, who testify that he has become irritated by certain types of questions that are difficult to answer, or by the time constraints imposed by television rules.

The appointment of González Urrutia was a small miracle: his name and his career emerged out of nowhere, in line with the current needs of the opposition. “When they surrounded me to ask me to take the candidacy, and they left me without any arguments, what I said to María Corina and the rest of the leaders present was: everything is great, now convince my wife that I am going to be a candidate,” González Urrutia recalls. Mission successfully accomplished: it is he and his daughters, as he himself admits, who accompany him and help him in all the details of the campaign. Even if he did not want it, even if he did not look for it, the hope of a part of the country that wants change falls on his shoulders.

Follow all the information from El PAÍS America Facebook And Xor in our Weekly newspapers,

(tags to translate)America