‘Solar Orbiter’ reveals never-before-seen images of the Sun taken at a distance of 74 million kilometers | Science

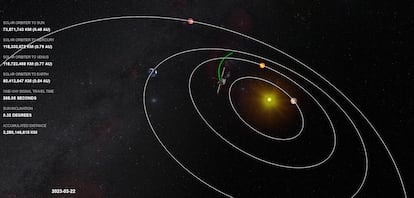

Deciphering the Sun is important because it is the source of life, as well as the source of phenomena such as eruptions and coronal mass ejections that affect communications, and a determining factor in Earth’s climate or in the planning of space missions or for the study of similar stars. Four years ago, the European Space Agency (ESA), with the support of NASA, launched Solar orbiterthe most complex space research laboratory of the main star in our system. Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and Ultraviolet imager (EUI) of the spacecraft will provide new unpublished images this Wednesday taken on March 22, 2023, less than 74 million kilometers from the star, fueling research and capping research taken a year earlier.

The new complete images of the Sun are the highest resolution yet and include maps of the magnetic field and surface motion. They can be observed in detail and with unprecedented close-ups on this portal provided by ESA. This was made possible by combining individual images taken over more than four hours by six instruments, allowing us to reveal the different layers of the star, the direction of the magnetic field, and a map of the speed and direction of the different layers of the star.

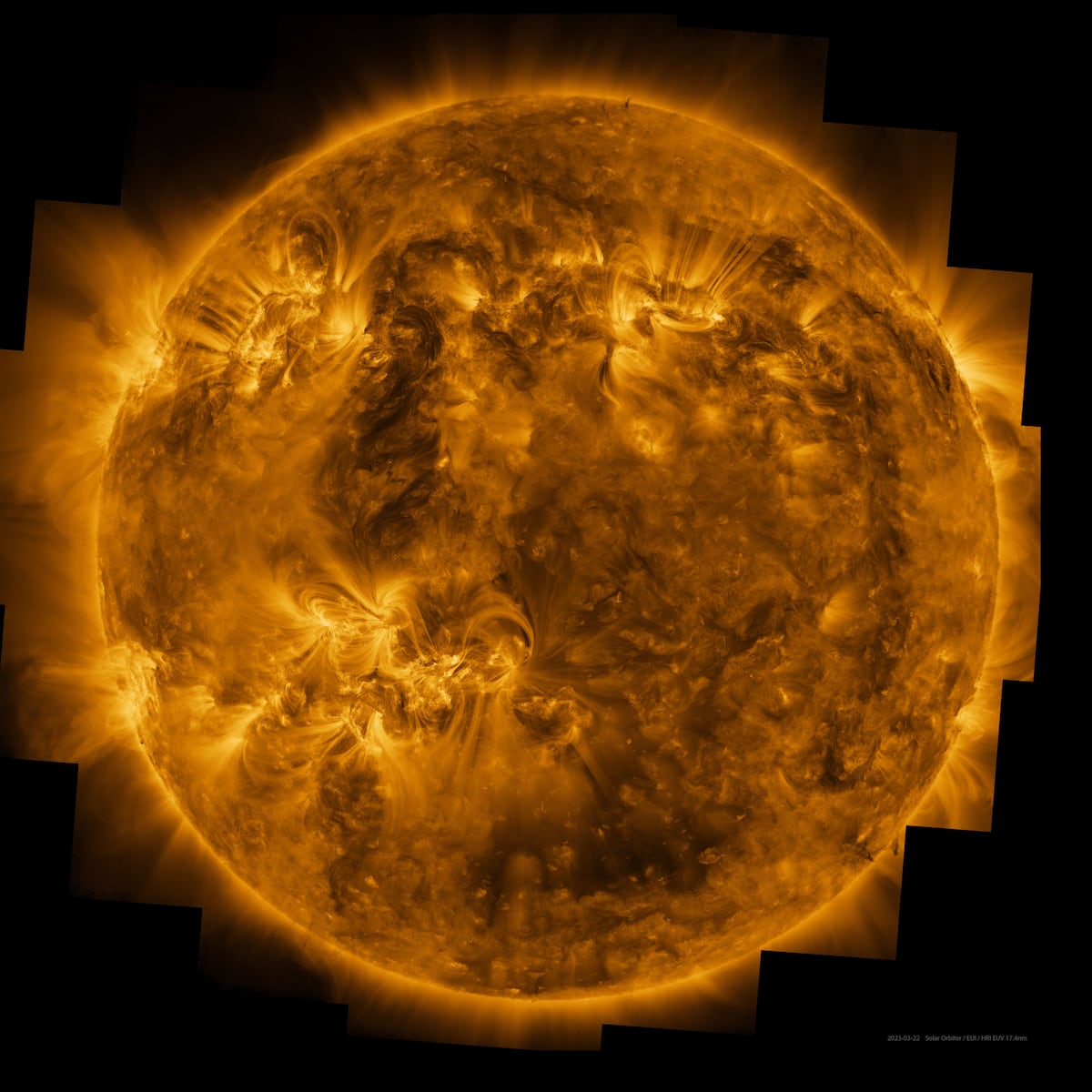

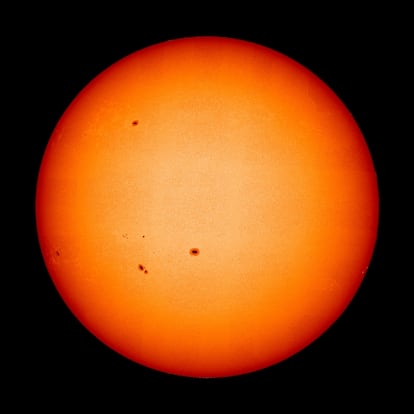

The image of the solar corona at the top of this information shows what is happening in the photosphere, the star’s atmosphere from which visible radiation comes. The photo shows sunspots in active regions and overhanging millions of degrees of plasma that follows magnetic field lines and in some cases connects adjacent sunspots.

“It is made at a wavelength of 17.4 nanometers,” explains David Orozco, a scientist at the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia (IAA-CSIC). “You can see plasma at over a million degrees in the photosphere towards the corona (the outermost part). We can say that this is an image of the temperature of the Sun, its visible part. What’s important is that you see a completely different structure with loops that respond to magnetic fields, like a magnet.”

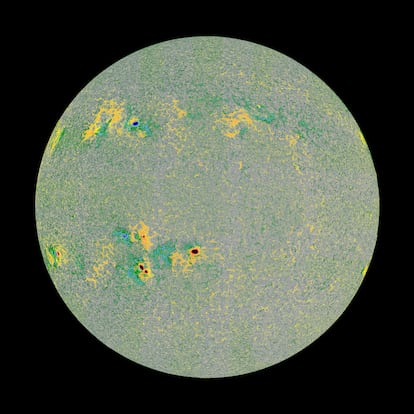

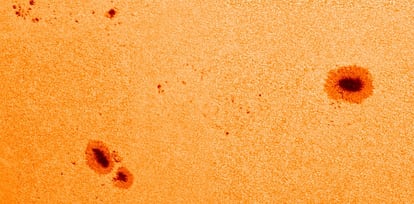

A magnetic map or “magnetogram” shows how the Sun’s magnetic fields are concentrated in sunspot regions and point outward (red) or inward (blue). The strong magnetic field explains why the plasma inside sunspots is cooler. Normally, convection transfers heat from the Sun’s interior to its surface, but this is hampered by charged particles that are forced to follow dense magnetic field lines in and around sunspots. “This is an image of the surface of the Sun, and you can see the magnetic fields concentrated in sunspots, in the most active regions. There are a lot of spots, but the ones marked yellow and green are weaker than the darker spots,” Orozco says.

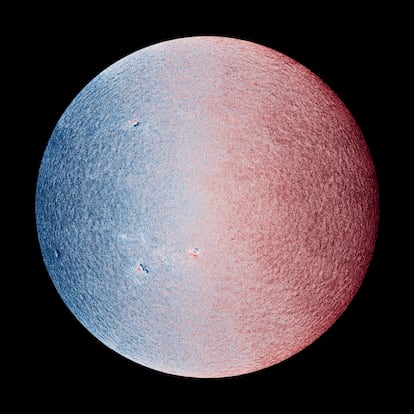

A tachogram is a map of the speed and direction of movement on the surface of the Sun. The blue color shows the bias towards the observer (in this case, the observer). Solar orbiter) and red – in the opposite direction. This map shows that although plasma on the Sun’s surface normally rotates in the direction of the Sun’s rotation on its axis, it is pushed outward around sunspots. “Although the image is static, the plasma is constantly moving across the surface,” explains Orozco.

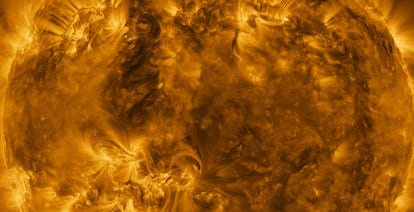

The visible light image shows the Sun’s surface as it is: bright, hot plasma in constant motion. This is where almost all solar radiation is generated, temperatures range from 4500 to 6000 degrees, and sunspots are cooler than the surrounding area and therefore emit less light. Below, plasma bubbles in the “convection zone,” not unlike magma in the Earth’s mantle. As a result of this movement, the surface of the Sun takes on a grainy appearance. In this photo, sunspots appear as dark areas or holes because, being cooler than their surroundings, they emit less light.

An astrophysicist from the Andalusian Institute calls “very important” the information provided by the Solar Orbiter, which he considers one of the most important instruments developed by ESA. “It’s not a satellite, but it travels around the solar system and provides images from different perspectives that help us model the entire magnetic field and solar climate much better.”

Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist, agrees: “The Sun’s magnetic field is key to understanding the dynamic nature of our star, from the smallest to the largest scales. These new high-resolution maps show the beauty of the Sun’s magnetic field and surface currents in great detail. At the same time, they are crucial for determining the magnetic field in the hot corona.”

In the same sense, Steph Yardley, a solar scientist at the University of Northumbria (UK), argues that “the variability of solar wind currents, measured on the spot spacecraft close to the Sun provides a lot of information about its sources, and although previous studies have traced the origins of the solar wind, this has been done much closer to Earth. when this variability is lost.” “Because Solar Orbiter is moving so close to the Sun,” he adds, “we can capture the complex nature of the solar wind to gain a much clearer understanding of its origins and how that complexity is driven by changes in different source regions.”

In addition, according to the Andalusian researcher, “the mission is starting to leave the plane of the ecliptic (the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere throughout the year as seen from Earth) and this means that we are about to start seeing the magnetic structure of the poles. We don’t know that, but we know it behaves differently.”

In this sense, ESA confirms that from now on it will be able to provide high-resolution images twice a year after processing them and knowing how to shorten the 19 months that until now included the entire process. To find out the spacecraft’s location, the space agency has a tool called “Where is Solar Orbiter?”

And this allows us to conduct a unique study of not only the main star of our system, but also stars similar to it. “What we’ve learned about our Sun can be applied to other stars that also emit stellar winds,” explains Samuel Badman of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.