Solar Orbiter mission reveals new images of the Sun at a distance of less than 74 million kilometers

Although the Sun governs many aspects of our lives, there are still many questions about the Sun, such as what is the mechanism for accelerating the solar wind or why the corona, which is the outer part of our star’s atmosphere, is so much hotter than its surface. To answer these and other questions, the European Solar Orbiter mission was launched almost five years ago, although it is still on track to achieve its main goal – to get so close to our star from a never-before-seen point to take pictures of it. poles, has been revealing valuable information for some time.

The latest are four images compiled from high-resolution observations made by the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) and Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) instruments taken on March 22, 2023, less than 74 million kilometers from Earth. PHI is the highest resolution comprehensive image of the visible surface of the Sun to date, including maps of the Sun’s disordered magnetic field and solar motion. surface. On the other hand, the image provided by EUI shows a bright and intriguing solar corona.

“The Sun’s magnetic field is key to understanding the dynamic nature of our home star, from the smallest to the largest scales. These new high-resolution maps from PHI Solar Orbiter show the beauty of the Sun’s surface magnetic field and fluxes in exquisite detail. At the same time, they are crucial for determining the magnetic field in the hot corona of the Sun, which our EUI instrument detects,” says Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist, in a statement.

Images one after another

Visible light image of the Sun

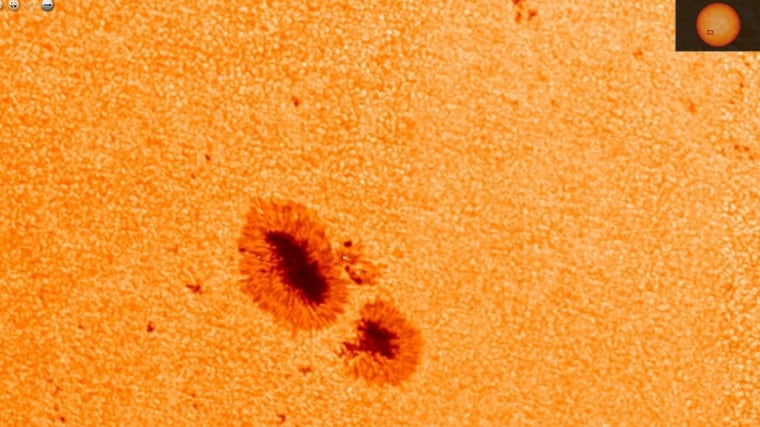

While PHI’s overall visible light image is impressive in itself, what’s most amazing about these images is that they allow for a zoom-in that shows the shape and boundaries of the spots as they appeared on our star at that time. Additionally, you may observe bright, hot plasma (charged gas) that is constantly moving.

Detailed image in visible light

Almost all solar radiation comes from this layer, whose temperature ranges from 4500 to 6000 °C. Beneath it, in the Sun’s “convection zone,” hot, dense plasma bubbles, similar to magma in the Earth’s mantle. As a result of this movement, the surface of the Sun takes on a grainy appearance.

However, the most striking thing in the photographs is the sunspots. When imaged in visible light, they appear as dark spots or holes on a smooth surface. Sunspots are cooler than their surroundings and therefore emit less light.

Magnetic map of the Sun

The PHI magnetic map shows that the Sun’s magnetic field is concentrated in sunspot regions. Move your cursor outward (red) or inward (blue) where the sunspots are. The strong magnetic field explains why the plasma inside sunspots is cooler: normally convection transfers heat from the Sun’s interior to its surface, but this is changed by charged particles that are forced to follow dense magnetic field lines in and around sunspots.

Direction of movement of surface material

The speed and direction of movement of material on the surface of the Sun can be seen on the PHI velocity map, also known as a “tachogram”. Blue shows movement towards the spacecraft, and red shows movement away from the spacecraft. This map shows that while plasma on the Sun’s surface normally rotates with the Sun’s overall rotation on its axis, it is pushed outward around sunspots (where, despite being in the blue zone, there are also red-colored regions).

Image taken under ultraviolet light

Finally, EUI’s image of the solar corona (the most superficial layer of the Sun’s atmosphere on its surface) shows what’s happening above the photosphere. Protruding bright plasma is visible above the active regions of sunspots. The million-degree plasma follows magnetic field lines that emanate from the Sun and often connect adjacent sunspots.

Difficult maneuver

Since Solar Orbiter was 74 million kilometers from the Sun, almost touching it in cosmic terms, the instruments were only able to capture a small part of our star. So full images were created from small pictures in which the spacecraft had to be tilted and rotated until every part of the Sun’s face was photographed.

To obtain the complete disk images shown here, all the images were stitched together to form a mosaic. The PHI and EUI mosaics consist of 25 images each, captured over four hours. The solar disk measures nearly 8,000 pixels in diameter when fully mosaiced, revealing an incredible amount of detail.

The image processing required to produce PHI mosaics was new and complex. Now that this has been done once, data processing and tile assembly will be faster in the future. The PHI team hopes to provide high-resolution mosaics twice a year.