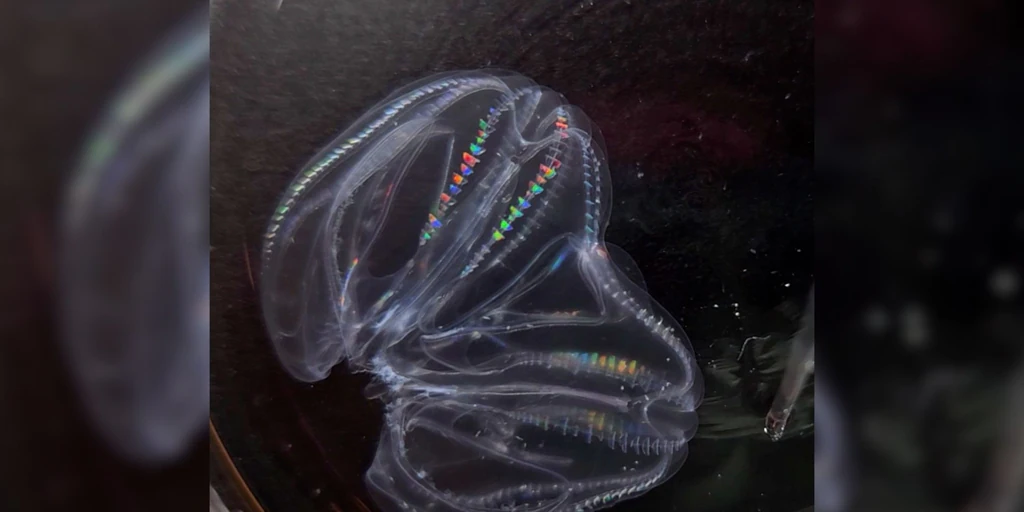

A jellyfish that, when wounded, merges with another and forms a single whole.

Just when you think nature can’t surprise you anymore, a team of Japanese researchers discovers something unusual: two specimens of the comb jellyfish (Mnemiopsis leidyi) can easily merge into one individual if they are injured. In a matter of hours, like something out of a science fiction story, they quickly synchronize muscle contractions and integrate digestive tracts to share food. There is no obvious separation between them, and the resulting jellyfish can survive for at least three weeks.

“Our results suggest that ctenophores may lack allorecognition, or the ability to distinguish between themselves and others,” says Kei Jokura from the University of Exeter (UK) and the UK National Institute of Life Sciences. (Japan). “These data imply that two individual individuals can rapidly couple their neural systems and share action potentials,” he adds. Their results are published this Monday in the journal Current Biology.

The comb jellyfish, also known as the bulb jellyfish, is actually a small carnivorous ctenophore with a transparent and bioluminescent appearance. Native to the western Atlantic Ocean, it is so invasive that it has spread to almost all European seas, including the coasts of the Spanish Mediterranean. The researchers maintained a population of these creatures in a seawater tank in the laboratory. They observed an unusually large individual that appeared to have two hindquarters and two sensory structures known as apical organs instead of just one. Surprised, they wondered if this unusual specimen was the result of the merger of two wounded jellyfish.

To find out, they removed partial lobes from other individuals and put them together in pairs. As it turned out, nine times out of ten it worked. The victims became one person and lived for at least three weeks.

startle reaction

Later research showed that after one night, the two original people became one. When the researchers pierced one lobe, the entire fused body reacted with “noticeable startle, suggesting that their nervous systems had also completely fused.”

“We were surprised to see that mechanical stimulation applied to one side of the fused ctenophore resulted in synchronous contraction of the muscles on the other side,” says Jokura.

More detailed observations showed that the fused ctenophores made spontaneous movements during the first hour. After this, the timing of contractions in each beat became more synchronized. After just two hours, 95% of the fused animal’s muscle contractions were completely synchronized. The digestive tract also joined. When one of the mouths ate the fluorescently tagged brine shrimp, food particles passed through the fused channel. The comb eventually removed waste products from both anuses, although not at the same time.

The researchers say it is still unclear how the fusion of two individuals into one acts as a survival strategy. They hope future research will help fill gaps in understanding, which could have implications for regenerative research.

“Allo-recognition mechanisms are related to the immune system, and neural fusion is closely related to regeneration research,” says Jokura. “Deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying this fusion could advance these important areas of research.”