Artificial intelligence resurrects giant molecules to create antibiotics | The science

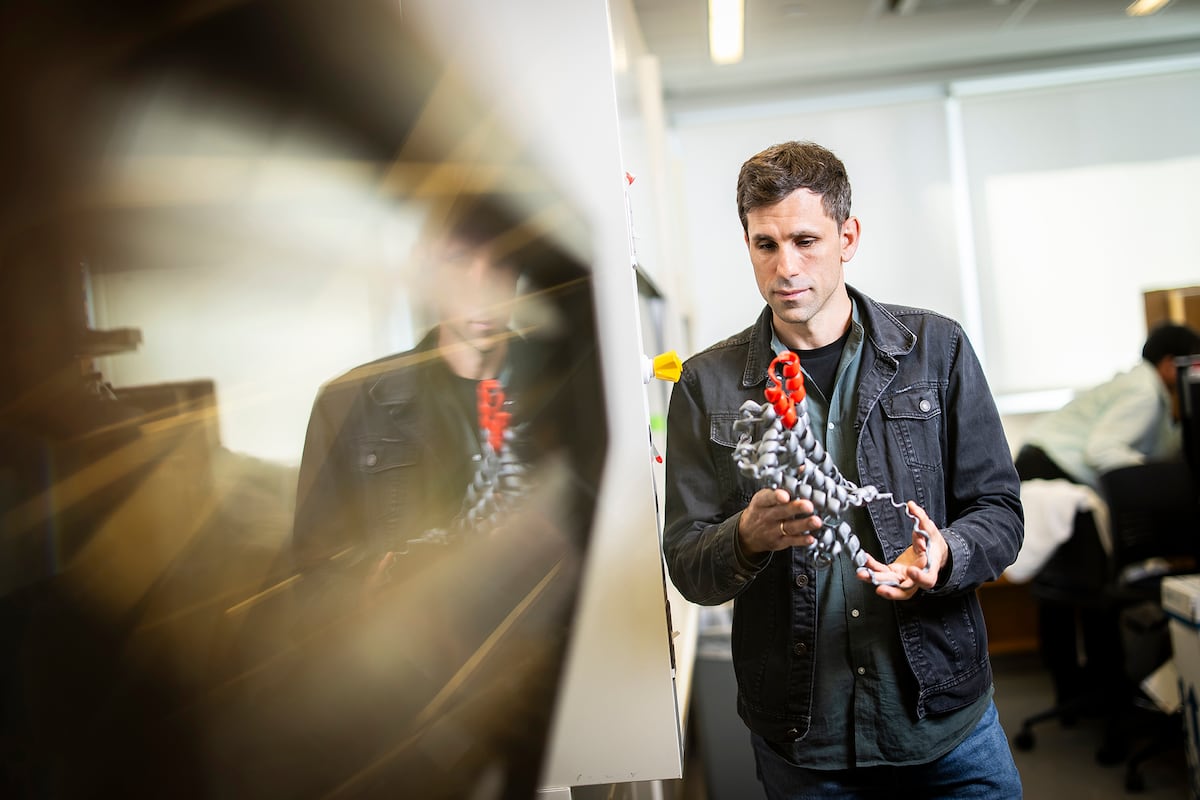

After a few years, death from frequent bacterial pneumonia or a common infection may become common. According to the study, of all the threats facing humanity, one of the top 10 is antibiotic resistance. World Health Organization (WHO). According to your specialized group (IACG), drug-resistant diseases could cause more than 10 million deaths annually by 2050, more than double the current figure. Spanish biotechnologist Cesar de la Fuente. principal investigator of the laboratory that bears his name, also known as the group Machine biology from the University of Pennsylvania, has been searching for more than ten years using artificial intelligence and deep learning (deep learning), new molecules that microorganisms have not yet learned to survive. He found them and resurrected them from our Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestors. Now, according to the publication Natural Biomedical Engineering, in extinct animals such as the mammoth. A race against time, in which everything may hide the solution: from missing species to microbial dark matter, microorganisms that have left genetic material in any environment but have not yet been grown in the laboratory.

If the rate of antibiotic resistance continues as before, human health will go back a century to the pre-penicillin era. Preventing this giant step backward is the mission of Cesar de la Fuente and his laboratory.

The discovery of compounds with antibiotic potential among Neanderthals and Denisovans opened the door for them to cross the border of the existing and search for extinct species. “This prompted us to ask the question: why not study all the animals, all the extinct organisms available to science?” explains De la Fuente, considered one of the top 10 researchers in the world.

The key is technology, the fusion of which with biology allows us to discover worlds that were hitherto hidden or have already disappeared. “To examine hundreds of proteomes (the complete set of proteins produced by an organism) simultaneously, we had to develop a more powerful artificial intelligence model than what was previously used. We create a model deep learning which combines the latest developments in the field of artificial intelligence and machine learning (machine learning) based on neural networks,” details the researcher, who calls the system APEX (Antibiotic peptide that restores disappearance o Renewed disappearance of antibiotic peptides).

“This allowed us to study organisms throughout evolutionary history, including the Pleistocene and Holocene periods. We study a variety of species, from extinct penguins to the mammoth or the giant sloth that Charles Darwin discovered on one of his expeditions to Patagonia,” he says.

This enormous effort recovered a total of 10,311,899 peptides (short chains of amino acids linked by chemical bonds) and identified 37,176 sequences with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Almost a third of them (11,035) are not found in existing organizations. “Because we are bringing molecules back to life that existed thousands of years ago, modern pathogenic bacteria have never disappeared. visible and they likely don’t have resistance mechanisms,” he explains.

Many of the sequences have demonstrated antimicrobial efficacy. in vitro (culture dishes or petri dishes), and some have been able to kill modern pathogenic bacteria in preclinical mouse models with efficacy comparable to that of currently available antibiotics and at lower doses. They have been tested on skin access and deep thigh infections.

Its origins, still unknown, even forced the team to develop new terminology. In the case of an extinct elephant ancestor, the small protein discovered is called mammothsin; the one who comes from Milodon Darwinia (ancestor of the sloth discovered by Darwin) Milodonin; And exusine This is the one found in the current zebra and its ancestors.

The team also experimented with combining multiple molecules of the same species or two similar molecules (a mammoth and an ancient elephant) in case they enhanced their antimicrobial activity against a single protein. It remains to be seen whether microorganisms will develop resistance to these new compounds and for how long. “He’s on the list,” De la Fuente says.

“This work allows us to go back in time and find different sequences, a diversity of molecules that can help us tackle antibiotic resistance and perhaps other problems. We always think about DNA to study life, but this work suggests we can start using molecules as sources of evolutionary information, see how they evolved or what types of mutations have occurred over time, learn more about our own immune system and perhaps predict how it will evolve,” he concludes.

The next step will be to formalize agreements with pharmaceutical companies and move beyond the preclinical level in mouse models to move on to human trials or even create a company emerging from the laboratory of Cesar de la Fuente to complete what has been achieved at the academic level.

Louis Ostrosky, head of the department of infectious diseases and epidemiology, UTHealth Houston (USA).University of Texas Health Science Center) and regardless of De la Fuente’s investigations, he praises the line taken in the face of an emergency that he considers real. “We are in a very dangerous time in the history of medicine as antimicrobial resistance is on the rise. In everyday medical practice, we encounter infections that cannot be treated with currently available antibiotics, and this is very serious since medicine depends on the use of antibiotics in routine procedures such as surgery, therapy or transplantation. “We are approaching a post-antibiotic era where we will no longer have effective resources and we are constantly looking for new ones.”

We are approaching a post-antibiotic era where we will no longer have effective resources and we are constantly looking for new ones.

Louis Ostrosky, Chief of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, UTHealth Houston

In this sense, the researcher trained at the National Autonomous University of Mexico defends all areas of research. “The best antibiotics we’ve ever had in the history of medicine came from nature,” he emphasizes, pointing to research on plants, insects and other animals such as sharks. “Such studies (research from the laboratory of Cesar de la Fuente) have always seemed very interesting to me. “We’re seeing antibiotics in extinct species that haven’t been present in nature for thousands or millions of years, so they haven’t been subject to evolutionary pressure,” he notes.

Ostrosky points out that a full-time career has additional challenges: “Antibiotics are not good business for the pharmaceutical industry because they tend to have very short courses: patients get better quickly, and in the pharmaceutical industry the money is in the chronicles of disease. We constantly see them leave the market after 10 years and come back and leave. “We need other types of incentives that will give us confidence that we will have the antibiotics we need in the future.”

The specialist points to government support, which is already implemented in Europe and the US, or a “subscription model” so that companies are not so dependent on sales and so that it represents a fixed incentive. “There are many economic models, but right now we definitely need to change the mindset in the pharmaceutical industry.” In this sense, he advocates a more active role for the World Health Organization and cooperation between North American and European agencies.

He defends this need because he believes the WHO warning is “correct” and “realistic.” “If no action is taken, we could see a world in which it is unsafe to have surgery or chemotherapy, reducing patients’ defences. “Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon to talk to some patients at the end of life who have incurable infections.”

You can follow ITEM V Facebook, X And instagramor register here to receive our weekly newsletter.