E. coli variant may cause antimicrobial resistance

The research team focused on ‘antimicrobial-resistant E. coli’ (the leading cause of human death due to antimicrobial resistance) us all over the world) defined mechanism in dogs that can render several classes of antibiotics ineffective.

The study, published in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology, opens up new avenues for treatment in both animals and humans and establishes clinical infections in dogs as an approach to public health surveillance.

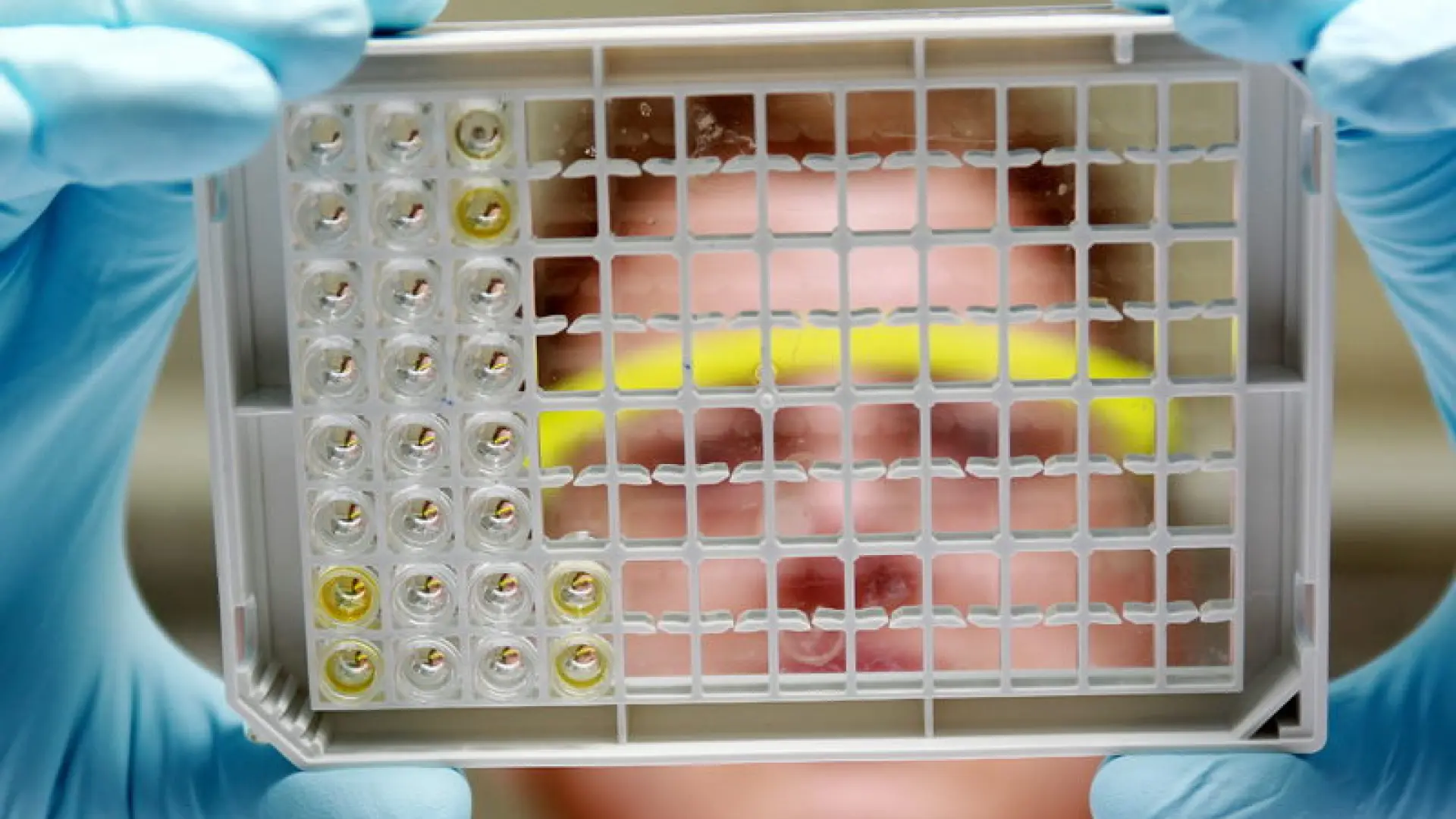

To reach this conclusion, a research team from Cornell University (USA) analyzed more than 1,000 genomes of resistant E. coli isolated from sick dogs and identified a set of genes that evidence of evolutionary selection showed were becoming obsolete in the genome and losing their function. But, surprisingly, loss of function could repurpose this set of genes to create conditions in which antibiotics are trapped in the E. coli cell membrane, preventing them from penetrating the bacteria.

“I like to think that this is a random event in evolution, because it looks like these capsule proteins have been repurposed to trap antibiotics.”” says Laura Goodman, an associate professor at Cornell University and lead author of the paper. “It appears that we are seeing a loss-of-function mutation that potentially produces a new phenotype unrelated to its original target.”

Not only could this study help improve dog health, it’s an example of how dogs serve as an important model for human health. However, dogs tend to have strains of E. coli similar to those of their owners, and are treated with similar antibiotics.

The World Health Organization considers two specific classes of antibiotics (third-generation cephalosporins and quinolones) to be critically important. Physicians and public health experts are particularly concerned about the overuse of these drugs in veterinary medicine; although there are no legal restrictions on their use in dogs, great efforts have been made to promote the proper use of these treatments.

The researchers hypothesized that the mechanisms affecting those drug classes identified in dogs would also be important in humans, Goodman says. “When we looked for this genetic variant in human infections, we found many of them in hospital and community surveillance data of E. coli and Klebsiella infections in humans.”

Now researchers can explore potential new drug targets that would prevent the pores in E. coli’s membrane channel from collapsing, allowing antibiotics to move freely inside the cell.

“The study is unique “as it provides mechanistic insight into antibiotic resistance and fills important gaps in surveillance of human E. coli infections using residual clinical specimens from dogs collected as part of routine care,” concludes Goodman.