Mosquitoes stalk us with infrared vision

Mosquitoes, in addition to other forms of detection, detect infrared body heat to locate humans, so loose clothing can help.

Although a mosquito bite is usually nothing more than a temporary annoyance, in many parts of the world it can be a source of fear. Something like a mosquito, Aedes aegyptispreads viruses that cause more than 100,000,000 cases of dengue, yellow fever, Zika and other diseases each year. Another, Anopheles gambiensespreads the parasite that causes malaria. The World Health Organization estimates that malaria alone causes more than 400,000 deaths a year. In fact, their ability to transmit diseases has earned mosquitoes the title of the deadliest animal.

Male mosquitoes are harmless, but females need blood to develop their eggs. It’s no surprise that how they find their hosts, including humans, has been studied in depth for over 100 years. Over that time, scientists have discovered that they don’t use a single signal, such as smell or temperature. Instead, they integrate information from multiple senses at different distances.

A team led by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has added another sense to the mosquitoes’ documented repertoire: infrared detection. Infrared radiation from a source with a temperature close to human skin temperature doubled the insects’ overall host-seeking behavior when combined with CO2 and human odor. Mosquitoes overwhelmingly gravitated toward this infrared source when searching for a host. The researchers also found out where this infrared detector is located and how it works at the morphological and biochemical level. The results are detailed in the journal Nature.

Among the signals mosquitoes use are the CO2 content in exhaled air, odors, sight, the warmth of our skin and the moisture in our bodies.

“The mosquito we studied, Aedes aegypti, is exceptionally adept at finding human hosts,” said co-senior author Nicolas DeBeaubien, a former UCSB graduate student and postdoctoral fellow in Professor Craig Montell’s lab. “This work sheds new light on how they do it.”

Infrared control

It has been proven that mosquitoes love Aedes aegypti They use several cues to locate their hosts from a distance. “These include CO2 in our exhaled breath, odors, vision, heat (due to convection) from our skin, and moisture from our bodies,” explains Avinash Chandel, a co-author of the study and now a postdoctoral fellow at UCSB in Montella’s group. “However, each of these cues has its limitations.” The insects have poor eyesight, and strong winds or the rapid movement of a human host can confuse their chemical tracking senses. So the authors wondered whether mosquitoes could detect a more reliable directional signal, such as infrared light.

Within a radius of about 10 cm, these insects are able to detect the heat emitted by our skin. And they can directly measure our skin temperature after landing. These two senses correspond to two of the three types of heat transfer: convection (heat carried by a medium such as air) and conduction (heat by direct contact). But thermal energy can also travel longer distances when it is converted into electromagnetic waves, usually in the infrared (IR) range of the spectrum. Infrared radiation can heat what it reaches. Animals such as vipers can sense the IR heat of warm prey, and the team wondered whether mosquitoes such as Aedes aegyptithey could do it too.

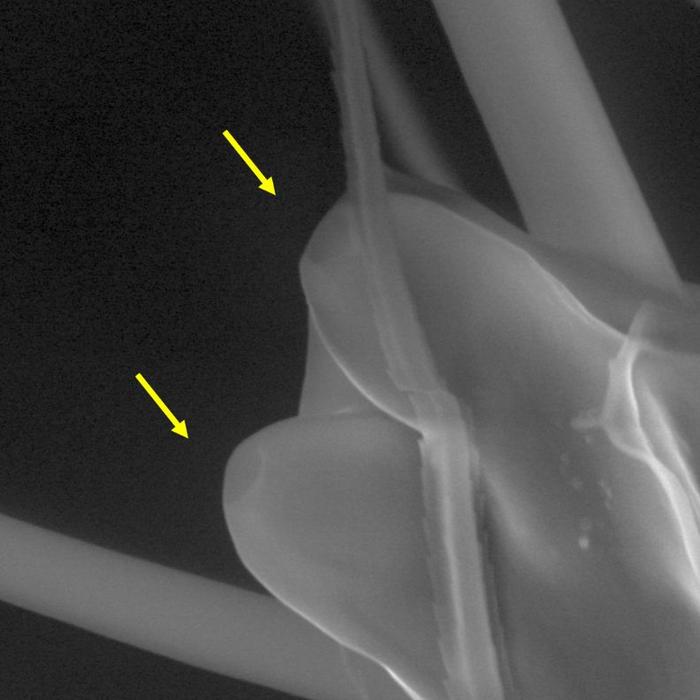

The pits at the ends of mosquito antennae protect pincer-like structures that capture thermal infrared radiation. Credit: DeBeaubien and Chandel et al.

The researchers placed female mosquitoes in a cage and measured their host-seeking activity in two areas. Each area was exposed to human odors and CO2 at the same concentration we exhale. However, only one area was exposed to infrared radiation from a skin-heat source. A barrier separated the source from the chamber and prevented heat transfer by conduction and convection. They then counted how many mosquitoes began to probe, as if searching for a vein.

Adding thermal infrared radiation from a source at 34° Celsius (approximately skin temperature) doubled the insects’ host-finding activity. This makes infrared radiation the newest documented sense that mosquitoes use to locate us. And the team found that it remains effective up to about 70 cm (2.5 feet) away.

“What surprised me most about this work was the strength of the infrared signal,” DeBeaubien says. “Once we got all the parameters right, the results were undeniably clear.”

Previous studies have not observed an effect of thermal infrared on mosquito behavior, but lead author Craig Montell suspects that this is due to methodology. A serious scientist might try to isolate the effect of thermal infrared on the insects by presenting only the infrared signal without any other cues. “But a single signal alone does not stimulate host-seeking activity. It’s only in the context of other cues, such as elevated CO2 and human odor, that IR matters,” says Montell, Duggan, a distinguished professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology. In fact, his team found the same thing in tests with only IR: IR by itself has no effect.

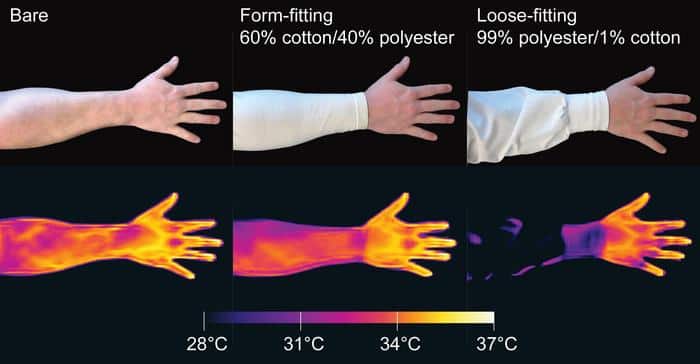

Loose clothing transmits less infrared radiation. Credit: DeBeaubien and Chandel et al.

Infrared Detection Trick

Mosquitoes can’t detect thermal infrared radiation the same way they detect visible light. Infrared energy is too weak to activate the rhodopsin proteins that detect visible light in the animals’ eyes. Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength longer than 700 nanometers doesn’t activate rhodopsin, and the infrared radiation generated by body heat is about 9,300 nanometers. In fact, no known protein is activated by radiation with such long wavelengths, Montell says. But there is another way to detect infrared radiation.

Let’s think about the heat emitted by the sun. The heat is converted into infrared radiation, which travels through empty space. When the infrared radiation reaches Earth, it collides with atoms in the atmosphere, transferring energy and heating the planet. “The heat is converted into electromagnetic waves, which are converted back into heat,” Montell explains. He notes that the infrared radiation from the sun has a different wavelength than the infrared radiation generated by our body heat, since the wavelength depends on the temperature of the source.

The authors thought that perhaps our body heat, which generates IR radiation, could affect certain neurons in the mosquito, activating them by heating them. This would allow mosquitoes to detect radiation indirectly.

Scientists know that the tips of mosquitoes’ antennae contain neurons that respond to heat. And the team found that removing these spikes deprived the mosquitoes of the ability to detect infrared radiation.

In fact, another lab had found a temperature-sensitive protein called TRPA1 at the tip of the antenna. And the UCSB team noticed that animals without a functional trpA1 gene, which codes for the protein, couldn’t detect IR.

The tip of each antenna has a pit design that is well suited for detecting radiation. The pit protects the plug from conductive and convective heat, allowing narrow-beam IR radiation to penetrate and heat the structure. The mosquito then uses TRPA1, which is essentially a temperature sensor, to detect the infrared radiation.

Delving deeper into biochemistry

The activity of the heat-activated TRPA1 channel alone cannot explain the range at which mosquitoes can detect infrared radiation. A sensor that relies solely on this protein would be useless in the 70cm range observed by the team. At that distance, there probably isn’t enough infrared radiation collected by the pin-on-pin structure to heat it up enough to activate TRPA1.

Fortunately, Montell’s group had hypothesized that there might be more sensitive temperature receptors based on their previous work in fruit flies in 2011. They found several proteins in the rhodopsin family that were highly sensitive to small increases in temperature. Although rhodopsins were originally thought to be purely light detectors, Montell’s group found that some rhodopsins could be activated by a variety of stimuli. They found that the proteins in this group were very versatile, involved not only in vision, but also in taste and temperature detection. Upon further investigation, the researchers found that two of the 10 rhodopsins found in mosquitoes were expressed in the same antennal neurons as TRPA1.

Deleting TRPA1 eliminated the mosquitoes’ sensitivity to infrared radiation. But insects with defects in either rhodopsin, Op1 or Op2, were unaffected. Even deleting both rhodopsins together did not completely eliminate the animal’s sensitivity to infrared radiation, although it significantly weakened the sense.

The results show that stronger thermal IR radiation, such as that experienced by a mosquito at a close distance (e.g., about 30 cm), directly activates TRPA1. Meanwhile, Op1 and Op2 can be activated at lower levels of thermal IR, and then indirectly activate TRPA1. Since our skin temperature is constant, increasing the sensitivity of TRPA1 extends the range of the mosquito’s IR sensor to about 60 cm.

Tactical advantage

Half the world’s population is at risk from mosquito-borne diseases, with about a billion people infected each year, Chandel explains. In addition, climate change and global travel have expanded the range Aedes aegypti outside of tropical and subtropical countries. These mosquitoes are now present in places in the United States where they were not present just a few years ago, including California.

The team’s findings could lead to better methods of suppressing mosquito populations. For example, using thermal infrared radiation from sources close to skin temperature could improve the effectiveness of mosquito traps. The findings also help explain why loose clothing is particularly effective at preventing bites. Not only does it prevent mosquitoes from getting on our skin, but it also allows the infrared radiation to diffuse between our skin and clothing so that mosquitoes cannot detect it.

“Despite their tiny size, mosquitoes cause more human deaths than any other animal,” DeBeaubien says. “Our research improves our understanding of how mosquitoes attack people and offers new opportunities to control the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases.”

LINK