Pion is the particle that explains why atoms don’t explode

If opposite charges attract and like charges repel… How can the protons that make up the atomic nucleus, be so together and not shoot back due to repulsion?

This question was more than repeated in the first third of the 20th century. The scientific community could not understand what was hidden behind the fact that the atomic nucleus did not explode. Was it power? Field? A particle they didn’t know about yet? The answer to this question was given in 1930 by the Japanese physicist Hiseki Yukawa: the solution was peonies.

WHAT ARE PEONIES?

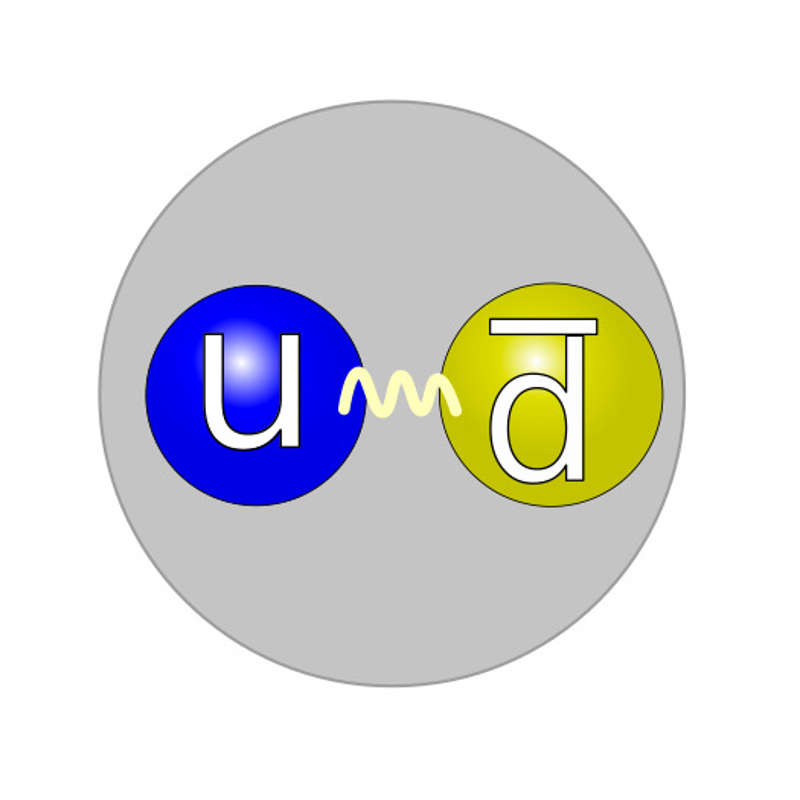

By pions we know a special type of subatomic particle known as a meson. To better understand what they are and how they work, we need to think of pions as small building blocks made up of even smaller components called quarks. These are very light particles with a mass of about 270 times less than that of a proton. In addition, they are very unstable: their half-life is only 26,033 nanosecondsThis means that after this short time, most of them will decay into other particles. In fact, this process typically produces a muon, another subatomic particle, and a muon neutrino, an even smaller and harder-to-detect particle.

A very characteristic property of these small particles is their spin. Simply put, we can think of spin as a kind of quantum property that determines the internal rotation of a particle. Well, peonies have zero spinthat is, they do not have this “spin” characteristic.

PARTICLE CONNECTING WITH A NUCLEUS

However, it is the ability to hold the nucleus together that is the most interesting property of these particles. In this context, we can say that a peony is a kind of “intermediaryin the strong nuclear interaction, that is, in one of the four fundamental forces of the Universe, along with gravitational, electromagnetic and weak interactions. This force is responsible for holding protons and neutrons together in the atomic nucleus: without the presence of pions, the core will explode due to the repulsive force that would exist between the protons.

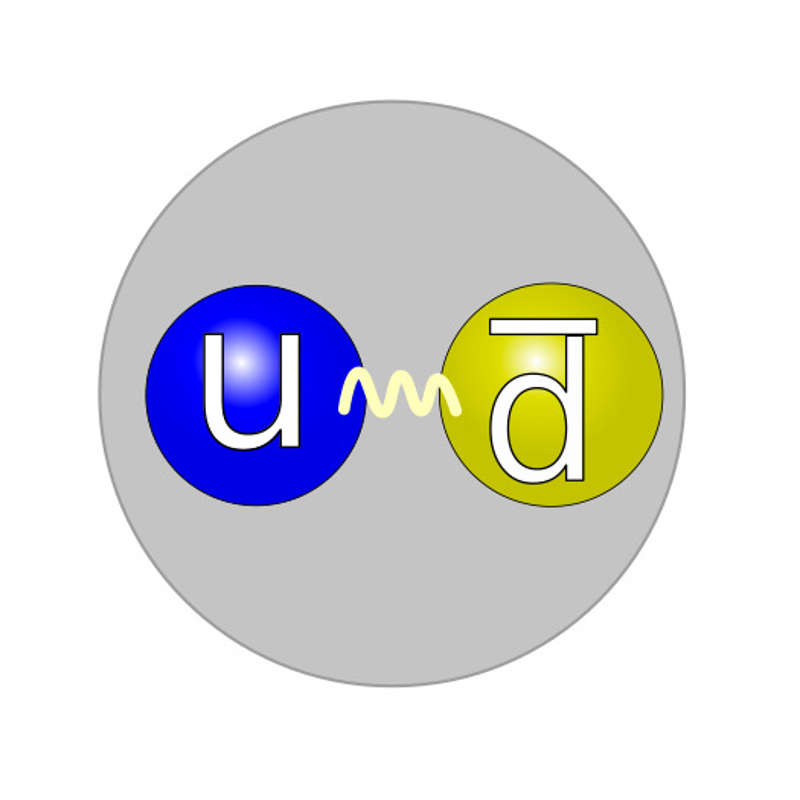

An “up quark” and an “anti-down quark” form a positively charged pion.

However, pions act as “messengers”, allowing, when a proton and neutron are close, they can exchange peonies, which creates a very strong attractive force that holds them together. So the stability of atomic nuclei becomes a really interesting topic: without pions, electromagnetic repulsion between protons – all with a positive charge – would lead to nuclear collapse. disintegrate; but thanks to pions and the strong nuclear interaction that arises between protons and neutrons as a result of the exchange of pions, nuclei can stay stable and shape the reality around us and ourselves.

And that’s not all: peonies also play a decisive role in stability of the neutrons themselves inside the core. But isolated neutrons are unstable and decay within 15 minutes. Now there are neutrons inside the nucleus much more stable due to the constant interaction with protons and other neutrons mediated by pions. This is due to the fact that the attraction mediated by pions manages to keep neutrons and protons in a state of dynamic equilibrium.

“INS”

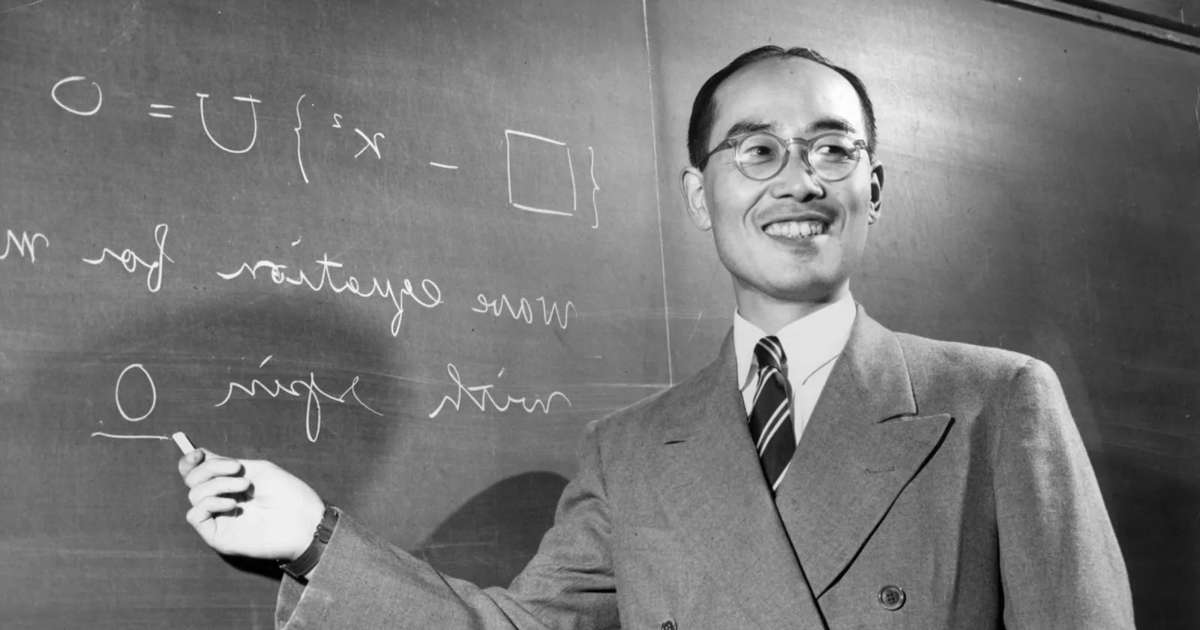

The discovery of this particle, the pion, was arguably one of the most significant moments in 20th-century physics. In the 1930s, the scientific community was focused on explaining what held protons and neutrons together in the atomic nucleus. Known forces, such as gravity or electromagnetic forces, They couldn’t explain this cohesion, especially since protons having a positive charge must repel each other. It was then that the Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa proposed a revolutionary solution: he proposed the existence of a new force acting through an intermediate particle and combining protons and neutrons. Yukawa called his little guess a “hotel.”

Yukawa’s idea was based on analogy with magnetic force. We know that this is carried out by photons, which are massless particles; Well, the physicist suggested that the strong nuclear force is also mediated in the same way, but by a particle with mass. It is this mass that would be the reason why nuclear force It will only operate over very short distances.on the order of the size of the atomic nucleus.

Hideki Yukawa gives an interview after receiving the Nobel Prize for the discovery of peony.

However, confirmation of this theory came only more than ten years after its prediction. In 1947, scientists Cecil Powell, Giuseppe Occhialini and Cesar Lattes, along with other colleagues, conducted a pivotal experiment in the Chacaltaya Mountains in Bolivia. They used emulsion plates exposing them to cosmic rays, high-energy particles from space. Analyzing the plates, scientists noticed traces of a particle that matched the characteristics of the meson predicted by Yukawa: it was peony.

BEYOND THE STANDARD MODEL

“One of the things that makes the discovery of the peony even more interesting is its origin.”natural”. The peonies discovered at Chacaltaya were created by the collision of cosmic rays with the Earth’s atmosphere, showing that these particles not only exist in laboratories, but are also part of the natural universe. More recently, traces of peonies were even discovered in supernova explosionswhich highlights its presence in extreme astrophysical events.

Hideki Yukawa received an award for his contribution Nobel Prize in Physics 1949.thus becoming the first Japanese person to receive such recognition in any scientific field. The discovery of the pion not only confirmed the theory, but also established a new paradigm in nuclear physics: it paved the way for the development Standard model, a theory that describes fundamental particles and their interactions. Although we now know that gluons provide the strong force at the quark level, pions are still critical to understanding the residual nuclear forces that hold nuclei together.