The Amazing Reason Why Insects Fly Around the World (Castile-La Mancha, Trapped in the Web)

It’s an observation as old as human gatherings around campfires: nightlight can attract hordes of randomly fluttering insects. In art, music and literature, this spectacle is a persistent metaphor dangerous but irresistible attractions. Watching their frantic movements really gives the feeling that something is wrong: instead of searching for food and evading predators, these night pilots become trapped by the light.

Although we have witnessed their behavior for centuries, we have little confidence as to why they do it. How is it possible that mere light turns swift and precise navigators into helpless captives and clumsy trembling men?

Our research team is studying flight, Vision And evolution insects, and we used high-speed tracking techniques in study recently published in Nature.

Moths towards the flame

Many of the old explanations for this hypnotic behavior have not yet come together. One of the first ideas was that insects were attracted to the heat of the flame. This was interesting because some insects are actually pyrophiles: they are attracted to fire and have evolved to take advantage of the conditions of recently burned areas. But most insects that hover around a light source do not fall into this category and are also attracted to cold light.

Another idea was that insects are attracted directly to light. behavior called phototaxis. Many insects move towards the light, perhaps to avoid darkness or traps. But if this were the explanation for the clusters around the light source, one would expect them to collide directly with the source. But this doesn’t happen. They don’t go straight into the light, but fly in circles.

The most romantic theory is that insects may mistake nearby light for the moon in an attempt to exploit celestial navigation. Many insects use the moon to help them stay on track at night.

This strategy is based on the fact that objects located at a great distance appear to be motionless while you are moving in a straight line. A stationary Moon indicates that you did not make involuntary turns, as would happen if you were hit by a gust of wind. However, closer objects do not seem to follow us in the sky, but rather lag behind as we move forward.

Celestial navigation theory posited that the insects sought to maintain the stability of this light source by turning sharply in an unsuccessful attempt to fly straight. It’s an elegant idea, but this model predicts that many flights would spiral toward collision, which typically doesn’t match the orbits we see. So what’s really going on?

We record thousands of flights

To study this question in detail, we took high-speed videos of insects around different light sources. We strive to accurately determine flight trajectories and body positions both in a laboratory at Imperial College London and at two field sites in Costa Rica, CIEE And Biological station. And we found that their flight patterns don’t match any existing model.

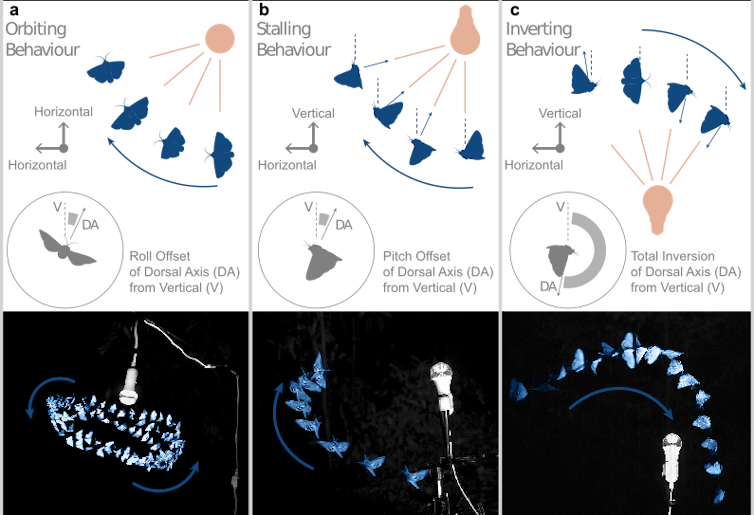

Rather, large numbers of insects systematically turned their backs to the light. This behavior is known as spinal reaction to light. In nature, assuming more light comes from the sky than from the ground, this response helps insects maintain the correct orientation for flight.

If they turn their backs to nearby artificial light sources, their flight path will change. They do something like airplanes where they tilt to turn, sometimes until the ground looks almost straight out of the window. When their backs are oriented toward a nearby light source, the resulting motion causes them to spin around the light, circling but rarely colliding.

These orbital trajectories were just one of the phenomena we observed. When insects flew directly under the light, they often arched upward as it passed behind them, keeping their backs to the light, until finally, flying in a straight line, they stopped and fell into the void.

And we discovered something even more unusual: When insects flew directly over a light source, they tended to flip upside down, turn away again, and then plummet.

Why turn your back to the light?

Although a night light can cause harm Other animals – for example, in divert migratory birds to urban areas– larger animals do not seem to lose their vertical orientation.

So why do insects, the oldest and most species-rich group of flying animals, resort to reactions that make them so vulnerable?

This may be due to its small size. Larger animals can feel gravity because they have sensory organs that sense their acceleration or any acceleration. For example, people use the vestibular system of our inner earwhich regulates our sense of balance and usually gives us a good idea of which way the ground is.

But insects only have small sensory structures. And especially when performing fast maneuvers in flight, accelerating only gives them a poor idea of where they are going. Instead, they seem to rely on the brightness of the sky.

Before the advent of modern lighting, the sky was typically brighter than the ground, day and night, so it provided a fairly reliable signal for a small active flier hoping to maintain a constant orientation. Artificial lighting, which sabotages this ability by causing insects to fly in circles, is a relatively recent development.

The growing problem of night lighting

As new technology spreads, lights pierce the night reproduce faster than ever. With the advent of cheap, bright and spread spectrumIn many areas, such as large cities, it is never dark at night.

It’s not just insects that are affected. Light pollution alters circadian rhythms and other physiological processes. animals, floors And Peopleoften with serious health consequences.

But insects trapped around a light source seem to have the worst of it. Unable to find food that is easy for predators to find and prone to exhaustion, many die before morning.

In principle, light pollution is one of the easiest problems to solve, often as simple as turning off a switch. Limiting outdoor lighting to warm, beneficial and targeted light, no brighter than necessary and for less time, can significantly improve the health of night-time ecosystems. And the same techniques that are good for insects help restore vision of the night sky: more than a third of the world’s population lives in areas where The Milky Way is never visible.

While insects circling the world are a fascinating sight, it’s certainly better for them and for those around them.the benefits they bring to humans that the night is dark and that we allow them to freely perform all those actions that they perform so masterfully under a sky in which the only thing that shines is the stars.

Samuel Fabian Postdoctoral fellow in bioengineering, Imperial College London; Jamie TheobaldAssociate Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University And Yash SondhiResearch Assistant in Entomology, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original.