The Phageome: The Hidden Kingdom in the Gut | Health and Wellness

You’ve probably heard of the microbiome – the multitude of bacteria and other tiny life forms that live in our gut. Well, it turns out that these bacteria have viruses existing in and around them, which has important implications for both them and us.

I present to you the phageome.

Inside the human digestive system are billions, perhaps even trillions, of these viruses, known as bacteriophages (“bacteria eaters” in Greek) or simply “phages” to their friends. The science of phagomes (also known as phages) has been advancing rapidly recently, says Breck Duerkop, a bacteriologist at the University of Colorado Anschutz School of Medicine, and researchers are struggling to understand its enormous diversity. Researchers suspect that if doctors could use or target the right phages, they could improve human health.

“There will be good phages and bad phages,” says Paul Bollyky, an infectious disease physician and researcher at Stanford Medical School. But at the moment it is still unclear how many phages live in the intestines: perhaps one for each bacterial cell or even less. There are also bacteria that contain phage genes but do not actively produce viruses; Bacteria live their lives only with phage DNA in their genomes.

And there are many phages that have not yet been identified; Scientists call them the “dark matter” of the phageome. An important part of ongoing phage research is the identification of these viruses and their bacterial hosts. The intestinal phage database contains over 140,000 phages, but this is certainly an underestimate. “Their diversity is extraordinary,” says Colin Hill, a microbiologist at the University of Cork in Ireland.

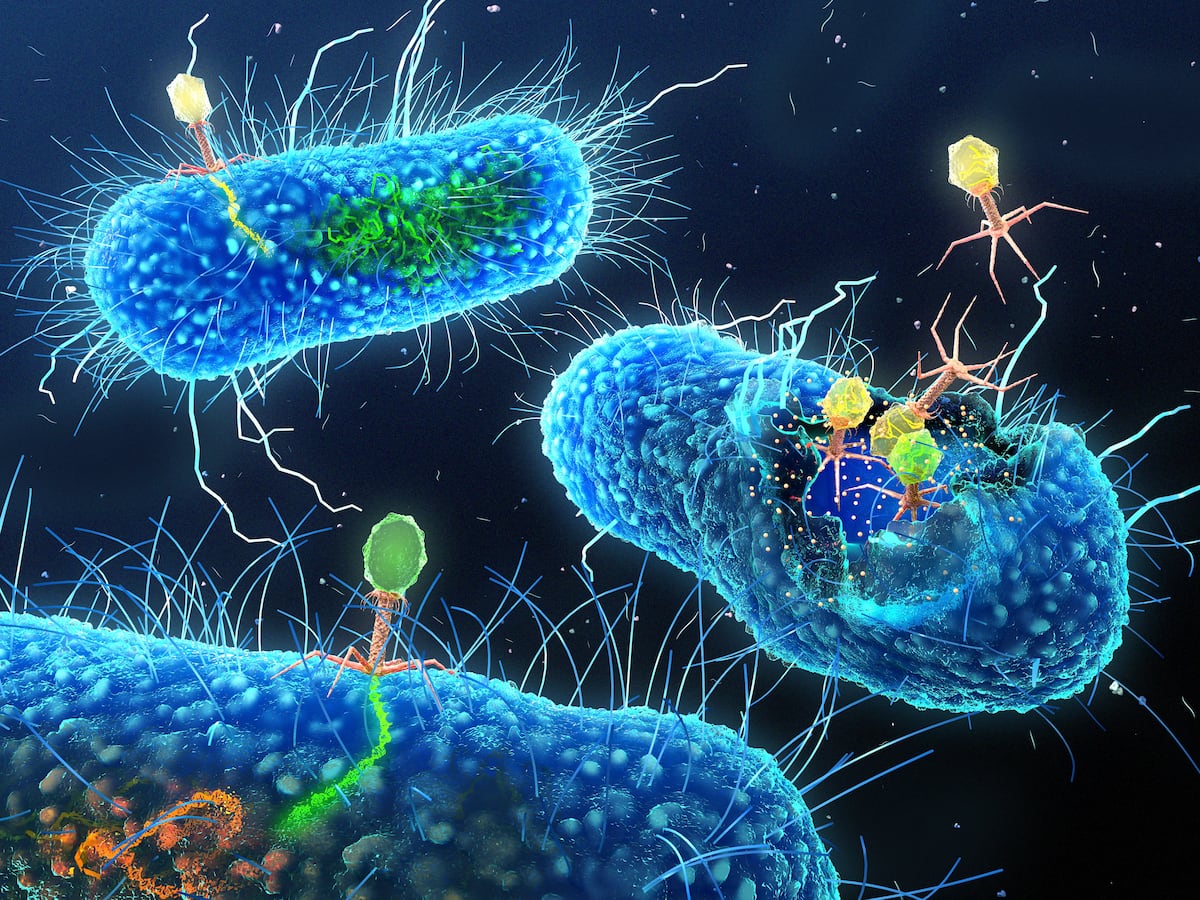

Scientists find phages by examining genetic sequences extracted from human fecal samples. It was there that researchers discovered the most common group of intestinal phages, called CrAss phage. Cross assembly phage(the name refers to the “cross-assembly” method that extracted its genes from the genetic mash). In a recent study, Hill and colleagues detailed the bulbous shape of CrAss phage with a 20-sided body and stalk for injecting DNA into host bacteria.

It is unclear whether CrAss phages affect human health, but since they infect one of the most common groups of intestinal bacteria, BacteroidesHill wouldn’t be surprised if they did. Other common groups that also infect to bacteroidesare Gubaphage (intestinal bacteroid phage) and LoVEphage (many viral genetic elements).

Phage varies greatly from one person to another. They also vary with age, gender, diet and lifestyle, as Hill and his colleagues describe in their paper. Annual Review of Microbiology 2023.

Although phages infect and sometimes kill bacteria, the relationship is more complex. “We used to think that phages and bacteria were fighting,” says Hill, “but now we know that they are actually dancing; They are partners.”

Phages can benefit bacteria by providing them with new genes. When a phage particle assembles inside an infected bacterium, it can sometimes introduce bacterial genes into its protein coat, along with its own genetic material. He later introduces these genes into a new host, and these accidentally transferred genes may turn out to be useful, Durkop says. They may provide antibiotic resistance or the ability to digest a new substance.

Phages keep bacterial populations in shape by constantly treading on their toes, Hill says. Bacteria Bacteroides There may be up to a dozen types of sugar coating on their outer surface. Different coatings have different benefits: for example, they evade the immune system or occupy a different part of the digestive system. But when there are CrAss phages around, Hill says, Bacteroides They have to constantly change color to evade phages that recognize one or another shell. Result: at any given time there are Bacteroides with different types of coverage allowing the general population to occupy different niches or face new challenges.

Phages also prevent bacterial populations from getting out of control. The gut is an ecosystem, like a forest, and phages are predators of bacteria, like wolves are predators of deer. The intestines need phages just as the forest needs wolves. When these predator-prey relationships change, diseases can arise. Researchers have observed changes in the phage of inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS), irritable bowel disease, and colorectal cancer; For example, the viral ecosystem of a person with IBS is usually not very diverse.

People try to balance the gut microbiome through diet or, in extreme medical cases, stool transplants. Studying phages could provide a better approach, Hill said. For example, scientists are looking for phages that can be used therapeutically to infect bacteria that cause ulcers.

Thank the trillions of phages that control your intestinal ecosystem. Without them, Hill suggests, certain types of bacteria can quickly take over, which can prevent you from digesting some foods and cause gas and bloating. The wild and wonderful phage is a dance partner for both bacteria and humans.

Translated the article Debbie Ponchner

This article originally appeared in Knowledgeable in Spanisha non-profit publication designed to make scientific knowledge accessible to everyone.