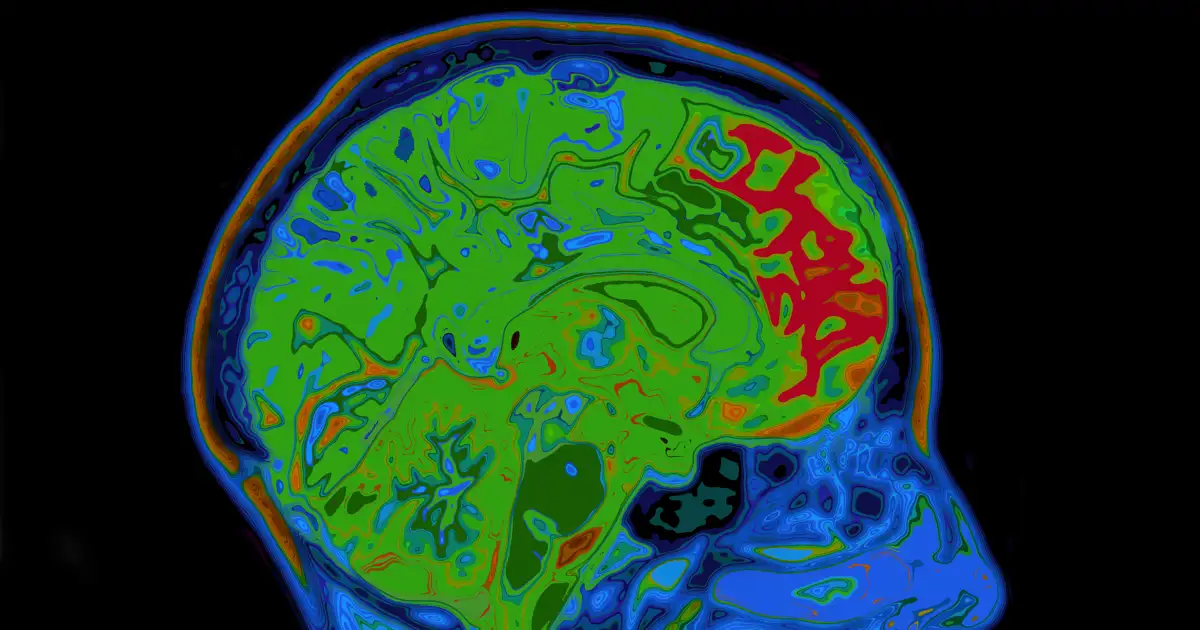

They are discovering that memories are not only stored in the brain.

The new discovery could revolutionize our understanding of memory.

A recent study published in Natural communications shook up the foundations of neuroscience by suggesting that memories are not only located in the brain, but also in other cells of the human body.

This suggests that the ability to store and process information This may be a phenomenon common to all cells, not just neurons..

In a study led by Prof. Nikolai Viktorovich KukushkinScientists have managed to reproduce one of the most fundamental principles of memory formation, the so-called “space effect” or mass diversity effectin two types of human non-neuronal cells.

To do this, they exposed cells to pulses of chemical signals and analyzed their response, finding that, like neurons, these cells can “remember” and respond differently when stimuli are applied intermittently rather than continuously.

Simulating “cellular learning”

The inspiration for this work comes from well-known phenomenon in neurobiology: The brain retains information better when learning is spaced out over time rather than concentrated in long, intense sessions.

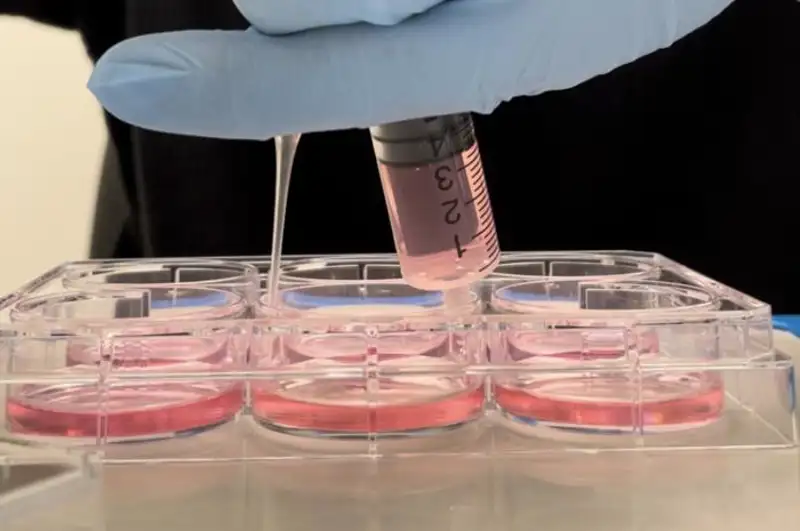

This study showed that cells in non-neuronal tissues also respond more strongly and persistently when they receive widely separated chemical signals. To model this “cellular learning,” the researchers pulsed certain compounds—forskolin and phorbol ester—on kidney tissue and nerve cells. triggering the expression of a glowing protein, indicating that the cell “remembers” the stimulus it received.

This change in molecular state is the equivalent of a “memory” that neurons activate when they detect patterns of information in the brain.

Moreover, this cellular response process involves the activation of proteins critical for memory, such as CREB and ERK, the inhibition of which interferes with the cell’s ability to respond to a separated stimulus. Essentially, this discovery suggests that memory does not rely solely on complex neural circuits. but may be embedded in the dynamics of chemical and protein signals common to different cell types..

Opportunities for medicine

This discovery opens up exciting opportunities for medicine and biotechnology. Understanding how these “cellular memories” work could help us improve treatments and develop innovative treatments for learning problems and memory disorders.

A New York University researcher transmits chemical signals to non-neuronal cells grown in a culture dish.

If all cells had a kind of “memory,” in the future we could use this quality, for example, to train cells of vital organs. so that they respond better to certain patterns or treatments.

Beyond the implications for neurobiology, this work raises interesting questions about other organs. Can the pancreas “remember” what you eat to regulate your blood sugar more effectively? Can a cancer cell “remember” chemotherapy doses to optimize treatment? These previously unexplored questions point to a future in which the body is viewed as a vast memory processing system, with each cell contributing to integrated functional knowledge.